Kōji – More Than Just a Sweet Thing

Anyone reading this has probably explained – or had explained to them – how sake is made at some point, and it usually goes something like the pithy line from the Kanpai Brewery in London: “brewed like a beer and enjoyed like a wine”. I never saw an explanation that didn’t refer to beer brewing, or more specifically malting… until recently.

The partnership between the Association de la Sommellerie Internationale (ASI) and the Japan Sake and Shochu Makers Association (JSS) mentioned in the previous article resulted in an educational sake tour for a group of selected wine sommeliers that took place in early 2023. Thanks to fellow wine expert Masakazu Minatomoto, General Manager of Kobe Shushinkan (Fukuju), the visitors never had to leave the comfort of their winemaking knowledge to understand sake brewing.

Minamoto’s description of the sake making process after yeast is added was the same comparison to winemaking you’ve no doubt heard many times before, but to explain what happens before that, he went even further back in the winemaking process… all the way back to the grapes on the vines.

Like all plants, grapevines derive their energy from photosynthesis. The vine stores sugars produced in the early growing season in its trunk and roots as carbohydrates. Then comes veraison, the start of ripening, when those carbohydrates are delivered to the developing grapes and turn into sugar. The similarity to kōji’s essential role of unlocking sugar from the carbohydrates in rice for sake brewing is obvious, and although Minatomoto didn’t explore it in his presentation, the parallels between kōji and ripening can be taken even further.

For example, the phrase ichi kōji, ni moto, san tsukuri (kōji is the most important, followed by the starter, then brewing) indicates the importance of kōji to the entire sake making process, and managing how grapes ripen and the timing of harvest is critical for the same reason - these processes establish the base that the sake brewer (or winemaker) has to work with.

You might think that the parallel with kōji falters here, as ripening is a natural process and making kōji is a carefully planned and managed series of human interventions. But there is just as much intervention in vineyards while the grapes are ripening, removing bunches to concentrate nutrients and sugars in the remainder, removing leaves to slow the production of sugars or leaving them on to create shade, even leaving grapes on the vine until they become as sweet and fruity as the winemaker needs.

This careful attention in the very final stage before adding the yeast is also shared between sake brewers and winemakers. Brewers fine-tune the development of their kōji to ensure they have the base they need to produce their desired sake, beautifully illustrated by the Tsuchida 99 STUDY set, made by Tsuchida Shuzo, from kōji allowed to grow for shorter or longer periods of time. “Muro time” could be the sake version of “hang time” for grapes left on the vine until they are just right to harvest.

You can also look at both kōji and ripening as a process of transformation. During ripening, small, hard grapes turn into large, soft fruit with thin skin. The acids and tannins that discourage animals from taking the grapes before seeds develop break down and become mellow. Glucose and fructose increase as green chlorophyll is replaced by colorful anthocyanins in red grapes, and translucent carotenoids in white grapes. Flavor and aroma also develop, turning from vegetal to fruity, and rising sweetness is balanced by the development of bitter or astringent flavonoids and polyphenols.

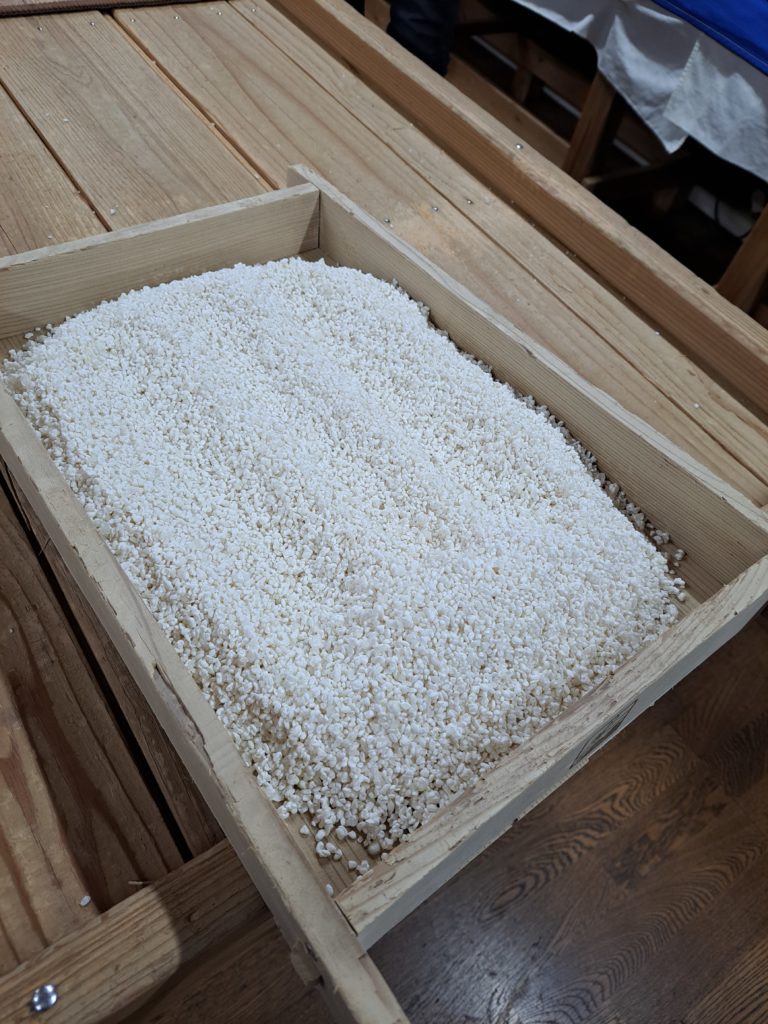

Kōji also physically and chemically transforms a hard substrate with unsuitable properties to prepare it for alcoholic fermentation, creating the components that give the final product its distinctive characteristics. Amylase enzymes produced by the kōji mold turn carbohydrates into sugar and break the rice grain down physically so it can dissolve in the main ferment. Proteases and peptidases act on proteins, creating both the umami and depth that are an essential part of sake’s flavor profile, as well as the bitterness and astringency that make it complex and complete. Kōji also produces a huge range of components that are taken up by or affect microbes in kimoto-type starters and yeast during alcoholic fermentation, so its role extends far beyond just producing sweetness and umami.

Grapes have been described as tiny biochemical factories, and although kōji is a separate microorganism grown on rice, you can appreciate how they act in similar ways. That extends to the people managing them as well – sake brewers create the perfect environment for their key microorganisms to thrive, while guiding them towards their desired result. Winemakers do something remarkably similar, starting with the grapes in the vineyard and carrying the fruits of that labor through to fermentation in the winery.

I was interpreting for the wine sommeliers on the tour, so I left Kobe Shushinkan with them to move on to the next brewery. Minatomoto was honored that his brewery had been chosen as their first stop, and that he was asked to give them the introduction to sake that would serve as the basis upon which the rest of the tour would build. Come and visit again, he urged me. Of course, I replied.

Masakazu Minatomoto passed away on April 22, 2023, on his way to judge at the International Wine Challenge in London. The last post on his Facebook page was the classic photo through the plane window as the flight was about to take off, complete with excited caption.

So, I can never keep that promise. I can go back to the brewery, to the giant barrel on its side in the garden where we all asked more questions, laughed and took photos together, but he won’t be there to welcome me with his calm smile, his deep well of knowledge, and his warm friendship. All I can do is share the ideas he shared with me, and pay tribute to his joy and skill as a teacher.

References

- Kobe Shushinkan https://www.we.enjoyfukuju.com/en

- “Veraison: When Grapes Turn Red”, Wine Folly https://winefolly.com/deep-dive/veraison-when-grapes-turn-red/ (accessed 22 August 2023)

- “Stages of Grape Berry Development” E. Stafne and T. Martinson, Grape Community of Practice https://grapes.extension.org/stages-of-grape-berry-development/ (published 20 June 2019, accessed 22 August 2023)

- “Do Grapes Change Color? Understanding Grape Veraison” Jordan Winery https://www.jordanwinery.com/blog/grape-veraison/#:~:text=The%20beginning%20of%20ripening%2C%20grape,start%20changing%20color%20until%20August. (accessed 22 August 2023)

- “6.3.1 Fruit maturity” in M. Keller, The Science of Grapevines (Third Edition), 2020

- “The 6 Keys to Veraison, the Adolescence of Grapes”, Pazo Baion https://pazobaion.com/en/keys-to-veraison/ (posted 3 August 2023, accessed 22 August 2023)

- “Understanding grape berry development” J. Kennedy, Practical Winery & Vineyard July/August 2002 https://jcast.fresnostate.edu/ve/documents/outreach/Understanding-page%2014.pdf (accessed 22 August 2023)

- “For returning kurabito only! Saku Toji Experience (3 days, 2 nights): Go Beyond the Kurabito Experience and See How Toji Manage the Moromi!” Kurabito Stay https://kurabitostay.com/en/booking-info/experience-info/202402tojiexperience/ (accessed 22 August 2023)

- “Episode of Tsuchida99 and Tsuchida99 STUDY”, Tsuchida Shuzo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6isehEFLoCE (YouTube video, 8:05, Japanese only, posted 15 September 2022, accessed 22 August 2023)

- “Formation of taste-active pyroglutamyl peptide ethyl esters in sake by rice koji peptidases” Ito et al https://academic.oup.com/bbb/article/85/6/1476/6171013?login=false Bioscience, Biotechnology and Biochemistry vol. 85, Issue 6, June 2021 (accessed 31 August 2023)

- “III. Kōji-kin, III-3 Seisanbutsu, A Kikōji-kin” (III. Koji mould, III-3 Products, A Yellow kōji) Kojigaku, Brewing Society of Japan, 1986

- Death notice for Masakazu Minatomoto, Kobe Shushinkan https://www.shushinkan.co.jp/news/kinkoku_minatomoto.html (posted 1 May 2023, accessed 22 August 2023)