Across a pair of recent episodes of Sake On Air, Wolfgang Angyal, CEO of the Riedel company in Japan, has prepared a brilliant workshop, an opportunity to understand Riedel’s methodology for devising and determining the shape of a glass vessel, as well as sample a selection of sake in Riedel glasses (wine glass, daiginjo glass, junmai glass) … and a traditional guinomi.

The point was not to settle upon what is “best” for sake, but about experiencing how the choice of the vessel impacts the tasting, through a number of factors: temperature, position of the head and shape of the mouth, flux, aromatic intensity.

As a follow-up to the recent episode, I wanted to to take a moment to reexamine some of the things we know about the history of sake-related glassware in Japan.

Until the beginning of the 18th century, glass had to be imported into Japan. Remember that this transparent material is not part of Japanese traditional architecture. While the first glass material was probably brought in from Korea, there are signs that an active glass-shaping craft took root across the Japanese archipelago, to produce comma-shaped beads for example, whose design is unique to Japan (one of the imperial regalia) and Korea, as early as during the Yayoi period (300BC to 300AD).

In the 8th century, one of the Silk Roads’ branches was ending in Nara, the then Imperial capital of Japan. The Shosoin Treasure Hall has splendid and precious glass-made drinking and serving ware which arrived from Persia around this time.

From the 16th century, Portuguese, Spanish then Dutch merchants brought European glassware into the country through their Nagasaki trading post (including wine glasses, bottles and decanters for daily use). Japanese were enthralled by such products, and glassware soon became popular items for upper class society.

Japanese started manufacturing glass in the 18th century using Chinese knowledge and technique, with the inspiration of Western design. By that time, the first Riedel family member had entered into the trade of luxury glassware in Europe, in Northwest Bohemia.

At a recent exhibition of selected inspiring ancient craft at Suntory Museum in Tokyo, glassware actually had a remarkable presence. I remember a gorgeous sake ewer with a handle and small series of beautiful blue, freely blown sake bottles dating from Edo times (1600-1868). They were almost perfect in shape, although not identical, showing that no mold was used. In addition they do not show the scar of the pontil rod, a tool used by European glass makers, that facilitates the production of blown glass. Such a rod enables the artisan to work on the mouth or handle of the piece while holding the shaped glass from the bottom. Because such technique was unknown in Japan, one can understand that these blue bottles, produced in large quantities, required considerable skill from the artisan! These bottles are known as “bidoro”, coming from the Portuguese work “vidro” (glass).

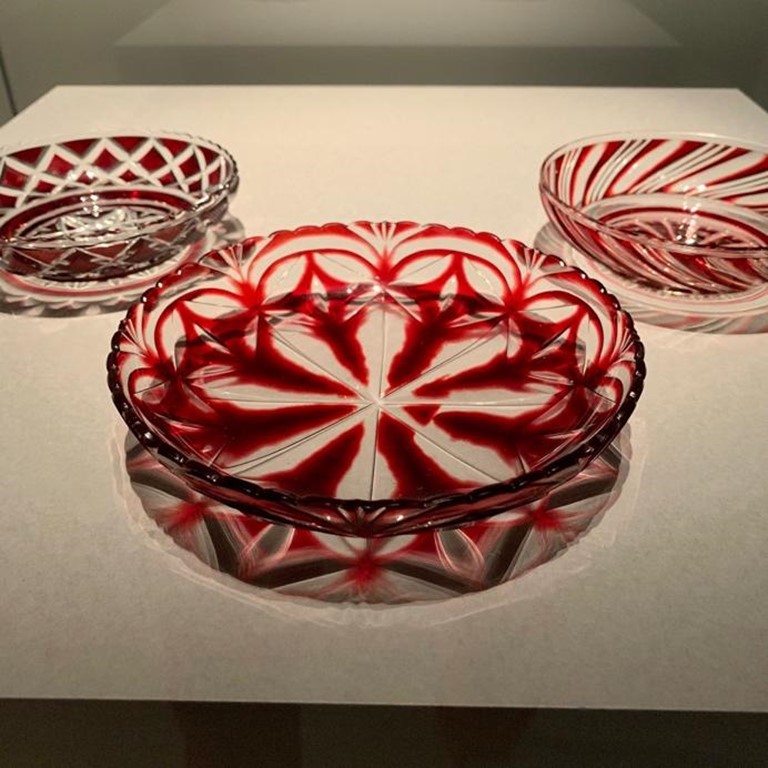

The first book describing glass making in Japan was published in 1829. In 1834, artisans developed a beautiful cut glass technique in Tokyo (known as Edo kiriko; Edo was the name of Tokyo before the Meiji Restoration), followed by Kagoshima in 1851 (known as Satsuma kiriko; Satsuma is the pre-Meiji name of the Southern Kyushu region, the name of the ruling clan). Satsumo kiriko is well known for its magnificent transparent red material (color produced by copper), and diverse motif compositions. European cut glass (Bohemia, England …) influenced the design, however, as often is in the world of arts, local craftspeople went one step further and developed a unique style. The Satsuma glass making workshops were burnt to ashes during the Anglo Satsuma war of 1863. Glass making was restarted in 1872, with beautiful objects sent to the Imperial Household, however specialists judge that Satsuma kiriko never fully recovered from this 10-year long interruption. The exhibition presented this boat shaped bowl with a bat on the stern (a symbol of good fortune), its wings outspread, and a tomoe motif (yin-yang double interlocking comma) on the prow. It probably had different usages, including this of a haisen, a bowl filled with clean water, placed between people drinking together, so that one could rinse (i.e. clean) the sake cup before passing it to the other.

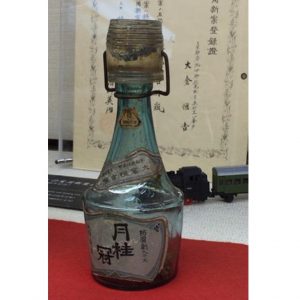

In 1910, Gekkeikan, a dynamic sake brewer from Fushimi (in Kyoto) introduced a small transparent bottle in the shape of a tokkuri, with an attached ochoko cap made from the same material, which was sold to passengers at train stations of the government-owned railway authority. According to the brewery, it gradually expanded nationwide over a few years, contributing to spreading the Gekkeikan brand, eventually becoming Japan’s largest sake producer. Until railways unlocked Kyoto sake from the former Imperial Capital’s limits, Nada sake (Kobe today) was the dominant sake “exporter” to the economic and political capital Edo. Today we can find sake bottles in many different colors. From the sixties, brown and green became most popular. Gekkeikan introduced brown sake bottles before 1927, to protect the drink against ultraviolets.

The use of large glasses, and stemware in particular, was inspired by the wine culture and is a recent phenomenon. Stems are rarely seen in Japanese table arts. The tradition remains influenced by the low tables where multiple plates are placed next to each other.

More to come on Sake On Air.

– Sebastien –

Reference: 1998BriefHistoryOf JapaneseGlass